The rise in bad loans in the education loan segment in 2013-2016 coincided with the Indian industry battling overcapacity, demand slowdown, stalling of new projects and defaults by top corporates.

Indian banks have seen a 142 per cent rise in default by students who have taken education loans during the past few years, at a time when hiring for new jobs has slowed down and tech companies have started laying off employees.

State-owned banks, which are already weighed down by huge defaults by corporates, are the worst hit as they account for over 90 per cent of educational loans. Private banks have largely stayed away from this segment.

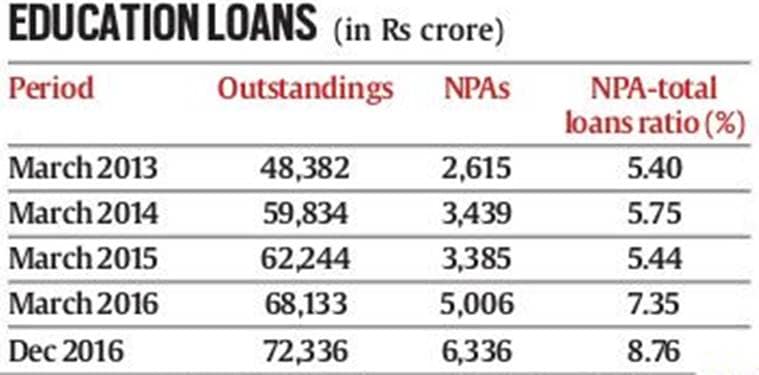

In the education segment, the total non-performing assets (NPAs), or loans on which borrowers have defaulted on payments for more than the stipulated 90 days, stood at Rs 6,336 crore at the end of December 2016, against Rs 2,615 crore in March 2013, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has revealed.

This is 8.76 per cent of the total education loan outstandings of Rs 72,336 crore as of December 2016, against Rs 48,382 crore in March 2013, the RBI said in a reply to an RTI filed by The Indian Express. Public sector banks began to disburse education loans in 2000-01. The concept was pushed the most by former finance minister P Chidambaram when the UPA government was in power.

The rise in bad loans in the education loan segment in 2013-2016 coincided with the Indian industry battling overcapacity, demand slowdown, stalling of new projects and defaults by top corporates. At the same time, the demand for loans was up as educational institutions, especially engineering and management colleges, mushroomed, without a check on quality.

More than half of education loans were taken by applicants in southern states, which have also reported most defaults. Students from Tamil Nadu and Kerala are in the forefront of taking loans, said an official of a nationalised bank.

Experts attribute the rise in defaults to the education scenario, pointing out that various state governments, especially in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, have approved setting up of educational institutions without considering the employment potential. “Two reasons for this (defaults). It could be that the students are not getting placed. And with engineers, this is highly possible. Second, they are not getting placed in jobs that they thought they would get placed in,” said Rituparna Chakraborty, president, Indian Staffing Federation.

With investments in new projects not taking off, there is an oversupply of qualified professionals. “Engineering is in a bad scene because most people in India want to become engineers and they thought that irrespective of their specialisation, they would get a job in the IT sector. And IT is not hiring and they are not inclined to hiring… My hope was that ‘Make in India’ would become a success and there would be some job creation, but that’s taking a little bit of time. Apparently there are no takers for engineers. There is an oversupply of engineers. Side by side, quality has also taken a backseat. That’s also impacting their prospects to get hired,” Chakraborty added.

State Bank of India, the largest player in the education loan segment, had disbursed Rs 15,716 crore to students by the end of December 2016. MD, SBI, Rajnish Kumar admitted that there was an NPA problem in the South, but added that they were ready to disburse under the fresh loans guaranteed by the Central government. In 2012, then finance minister Pranab Mukherjee had announced a Credit Guarantee Fund in the Budget to cover loans up to Rs 7.5 lakh without any collateral security and third-party guarantee. Various state governments, including Kerala, had announced their own schemes to repay the loans of students.

“Overall we are comfortable with the segment,” said Kumar. “We are ensuring the quality aspect also. We have an education scheme for students going abroad… these are all high-value loans. We are open to it. Unlike in the past, we are trying to ensure the quality of the loan.”

Central Bank of India Chairman and MD Rajeev Rishi admitted a problem with recovery earlier, but said things were improving. “In the initial phase when education loans were launched, we faced some problems, but not any longer. There’s no cause for concern. Normally people don’t cheat. They have a full career ahead of them,” Rishi said.

Bankers and financial sector firms say it’s the small-ticket loans which could turn bad. “There are a lot of new colleges and courses which keep coming up in India. Those colleges and courses need to be evaluated for their potential employability before lending. Banks don’t have time to do it and they find it difficult because it’s focused work and research is required. Most of the delinquencies are in the smaller-ticket loans which are being given for Indian courses. It’s directly proportional to the quality of education. If the quality of the course is not good, students will find it difficult to get the right job and right salary. Then it becomes difficult for them to repay loans,” said Prashant Bhonsle, CEO, Education and Housing, Incred Finance.

Banks also often find it difficult to track students who borrow money. “Operationally, after the course, the student gets a job in a different city. So it becomes difficult for the bankers to track the students,” he said.

At the same time, Bhonsle said, educational loans have started attracting new, specialised players. “ A lot of new players are looking at this segment as a large opportunity. They are trying to understand how to underwrite risk… You need to know about the university, college and course… whether they are good or not. You need to innovate and fit the right product to the right student profile, course profile and right parents profile.”

[“Source-indianexpress”]