Looking at the annual results of Alphabet, you could be forgiven for thinking that last year’s reorganisation of the world’s most valuable company was all for nothing.

Google, which is a subsidiary of Alphabet, dominated financially. The segment, which includes most of the best-known Google products such as its search engine, maps, Gmail, YouTube and Android, made up $74.5bn of the company’s $75bn (£52bn) annual revenue.

By contrast, every other subsidiary of Alphabet was reported in the results as “other bets”, with a total income of $448m – and an overall annual loss of $3bn.

But just because the projects do not bring in much money, it does not mean they have no effect on the company’s performance. If anything, it is the opposite: Alphabet is now the largest company in the world not because of the money it makes today, which pales in comparison to the former reigning champing Apple, but because of the money it could make tomorrow, the day after, or in 50 years.

Buried among the “other bets” are Alphabet’s secret weapons: X projects – “moonshot” investments that could change the world.

Immortality

The world of medicine could be changed forever if one of Google’s bets pays off.Calico, which stands for California Life Company, wants to “cure” ageing.

It sounds like a fool’s errand, but it only takes a small tweak in mindset to see why some might view it as a fight worth having: ageing is the single biggest cause of death and disability in the world, and yet, unlike every single other cause, it is viewed as inevitable.

A world where Calico succeeds in its goal of identifying and treating the underlying causes of ageing would represent the single greatest leap in healthcare since the discovery of antibiotics in the early 20th century. Critics point out that it would also remove one of the major factors keeping humanity from a crisis of overpopulation. But would you commit yourself to ageing and death if you could avoid it? And if not, how can you ask others to do so?

Of course, one other thing would happen if Calico’s gamble pays off: Alphabet’s profits from the medical industry would make its technology business look like small change.

Super spoons and smart eyes

These days, when we think of medicine, our minds turn to pills and syringes, in hospitals and doctors surgeries. But one Alphabet subsidiary, Verily, is taking a gamble that the future of medicine looks a lot like the future of tech.

Taking the trend of connected medical devices such as fitness trackers and implantable blood-sugar monitors to their logical conclusion, the prototypes developed by the company are gadgets that could change people’s lives for the better.

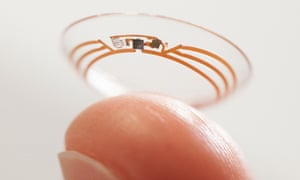

The company hit headlines in 2014 for revealing a smart contact lens, which aims to measure glucose levels in tears, permanently removing the need for invasive blood tests for diabetics. A few months later, it revealed a smart spoon: stabilised cutlery to help Parkinson’s sufferers eat.

Imagine going to the doctor’s surgery and being handed a slim black wristband that monitors your vital signs and feeds back minute-by-minute data to the GP and pharmacists so they can adjust your dosage, call you back if it gets worse – and check that you’ve been doing enough exercise.

Vitruvian Man 2.0

Not everything Verily is building is hardware. Its other major goal is to complete the “baseline study”: an attempt to map a healthy human body, in its entirety.

The project is collecting every sort of biological data possible, from genetic to anatomic, from physiological to psychological, in an attempt to build a chimeramodel of what a healthy human looks like. The short-term goal is to use the model to identify deviations far sooner than they can currently be picked up, and ultimately identify problems like cancer and heart disease when they can be prevented, rather than cured.

Connected world

Not every project is as wild as trying to cure death. But even the smaller ones could alter our relationship to the rest of the world. Project Loon is one example: it represents the company’s attempt to bring internet access to rural communities through a network of weather balloons, floating in the stratosphere, acting like ultra-low-cost satellites.

The project is in direct competition with a similar plan from Facebook’s internet.org, which aims to use solar powered drones to fulfil the same goal. And if either project pays off, it will usher in a world of genuinely ubiquitous connectivity: there will be nowhere on Earth that is offline. So telling your boss “I was in the middle of the Amazon” just won’t cut it as an excuse.

Robots at home – and at war

Boston Dynamics was acquired by Google in 2013. It had initially existed largely as a contractor for the US military, developing machines that can walk on rugged terrain. The BigDog quadrupedal cargo robot was the outcome: built like an ox, and walking with an unearthly whirring sound, even in its prototype form it demonstrates unnerving surefootedness. Unfortunately, they are too noisy for the US marines, which cancelled a contract with Boston Dynamics in December.

But the company is also looking at non-military uses of its robots, and has committed to taking no further contracts from the US Department of Defense. So what’s the first outcome? Atlas, a 150kg, 1.8 metre tall bipedal robot – that can do the hoovering.

Using a human shape is pretty inconvenient in robot design, because it turns out it is quite hard to balance on two legs, but our vanity means we keep on building them anyway. And so keep an eye on Boston Dynamics for your best hope of a Google-powered robot butler in the future. Hopefully, they will have dealt with the noise by then.

And all powered by the wind

All of this technology is of little use if it is driven by carbon-belching power stations that will melt the ice caps before we even sit behind the wheel of a self-driving car. So Makani, another X project, aims to create ubiquitous wind power, available wherever the air moves.

Their current prototypes look like a cross between a kite and drone, sitting at the end of long cables circling in the air. Their lightweight construction means they can operate where a traditional windfarm cannot, and be put up for a fraction of the cost. Their height allows them to reach high winds more than 300 metres in the air.

[Source:- theguardian]