Harvard Art Museum

“Waiting for cirrhosis to happen to treat HCV is like waiting for cancer to metastasize or for diabetes to cause complications before treating it. In reality, all cause mortality and per patient per year health care costs are tripled for patients with hepatitis C, whether they have cirrhosis or not.”

— Dr. Douglas Dieterich, leading hepatitis C and liver diseases researcher and specialist at the Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City

My friend John is a retired college professor who lives on a budget. He has hepatitis C, which he acquired from a blood transfusion before the development of blood testing and screening for hep C. He does have health insurance, but like most of those seeking treatment for this condition, he has been told that he must become demonstrably sicker to qualify for treatment coverage. Meanwhile, he must not drink any alcohol and remain vigilant for symptoms, especially fatigue. Since the progression of hepatitis C to cirrhosis of the liver and cancer of the liver can take decades, and John has already had this disease for decades, he is understandably concerned. In fact, he may die sooner from other causes, his untreated hepatitis C playing an indeterminate role. There is, however, an alternative for John. If he had the $100,000+ in cash to pay for the treatment now, he could be fully and safely cured in 8-12 weeks. John does not identify himself as a socialist, and he is willing to pay what he can for treatment, but the cost in this case is overwhelming.

Another friend, Alex, is a health care worker who contracted hep C sexually. He has had the identical experience as John in facing $100,000 pricing for insurance noncoverage in the absence of being demonstrably sicker. Recently, however, he had a stroke of luck. Through connections, persistence and good fortune, he managed to obtain one of a limited number of assistance vouchers from one of the drug companies that essentially entitles him to full coverage. Needless to say, he’s elated. Otherwise an articulate critic of corporate for-profit medicine, he can’t help but feel as if he just won the lottery.

Hepatitis C is a disease that leads to cirrhosis and cancer of the liver and death in large numbers of people. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that 350,000 to 500,000 people die each year of liver-related diseases from hepatitis C. In 1999, I wrote a feature on hep C for New York magazine called “C Sick” on what was then being called “the stealth epidemic,” for which I interviewed Dr. Dieterich at length. Because the vast majority of those with the disease in this country had acquired this viral scourge via injection drug use, it was very difficult to arouse the greater public to any kind of action or even concern.

And there seemed little hope for developing more successful treatment because profits seemed more questionable for a disease, at least in this country, that is mostly limited to people with histories of drug use. Like the gay men with AIDS who were treated so abominably by Reagan era health care policies and systems, those with histories of injection drug use not only had the same experience with AIDS, they, and a growing number of gay men along with them, are experiencing comparable medical neglect and abuse around hep C.

So beneath the public radar was hep C, and for so long, that most of those who had it didn’t know it. They were never tested and didn’t know they should be. One of the biggest concerns motivating my investigation had to do with identifying hep C as an STD in gay men, who weren’t even being encouraged to be tested. Fifteen years later, it is now finally acknowledged that hep C is seen as an STD in gay men, but sexually-active gay men still need to be informed and proactive enough to demand to be tested by their doctors, whose knowledge of hep C can still be surprisingly rudimentary.

Although it has taken many years longer than it should have to get there, testing for hep C is now more routine and there is more public discussion. Almost everybody has now seen advertisements for hepatitis C treatment on television. They’re strange. They show well-groomed, middle class, middle-aged people who look hopeful and trusting, but the information accompanying these images is opaque. They say things like “there is treatment now,” and they encourage those with the disease to “make further inquiries.” As with virtually all other pharmaceutical advertisements, nothing is said about cost.

The latest of these advertisements makes it a lot more clear that, in one of the biggest and most important developments in the history of medicine, hepatitis C is now fully curable in the great majority of cases with only 8-12 weeks of treatment with medications that have few side effects. Not one of these advertisements, however, hints at the staggering price tag of $1,000 a pill.

Who can afford this? For pharma (the pharmaceutical industry) that’s not the main question. The main question is how much will Medicare, Medicaid or other insurance pay for these drugs? In far too many cases, such as those in V.A. (Veterans Administration) systems, the answer is none.

The overview is this. Many people who can’t afford these medications, which in this country means the majority of cases, are not out of the running to receive them, and some insurance will pay for them, but in most of those cases, treatment is being delayed until there is serious disease progression — to fibrosis and early stages of cirrhosis, even though such delays place these patients at greater risk for cancer of the liver and other conditions. Once progression is demonstrated to be well underway, some insurance companies will then pay the costs for the new hep C treatments. While those costs are high, they are a lot less than what a liver transplant would cost them, which is the only other treatment option for end-stage cirrhosis and liver failure. In other words, the insurance companies are not paying for these treatments out of the generosity of their hearts so much as because they will likely have to pay a lot more if the disease progresses to liver failure and cirrhosis.

In my field of addiction medicine, and as anticipated, hepatitis C has eclipsed AIDS as the leading cause of treatable illness and preventable death. More than 90 percent of the nation’s 300,000+ patients on Methadone Maintenance treatment for opioid dependence are hep C positive. Many of them have Medicaid. While some of those with advanced disease are now being treated, the majority have lesser disease and, like my friends John and Alex, are not yet considered eligible for treatment, though they do have the option of initiating lengthy appeals of insurance coverage denials and may hold out some hope for obtaining assistance vouchers from the drug companies. Meanwhile, as Dieterich put it, telling patients they must put off treatment for hep C is like telling diabetes or cancer patients to hold off on treatment until the diabetes or cancer is more advanced.

And there is another consideration regarding the treatment of hep C patients with histories of injection drug use. The earlier they are treated, the less likely they are to spread hep C to others via relapse.

If not for insurance and cost issues, those who, like John, Alex and those in treatment for opioid dependence, have the most to benefit from it now can’t get it unless they are willing to pay for it. Most people have no way to pay such fees, but some do and others can go into debt. Cumulatively, the numbers of those who can get the money however they can are apparently enough to have swayed pharma to further leverage its collective soul by engaging in such devious financial schemes.

Remember Nixon’s “war on cancer”? Well, some of the life-saving cancer-treatments that were then just pipe dreams are now reality. The problem is that most of those who need these newest and most effective drugs to save their lives are having to give up all their assets in order to afford them, to the extent of declaring bankruptcy.

As spelled out by leading cancer specialists in an expose on 60 Minutes (originally broadcast 10/5/14 and updated 6/21/15), cancer costs are now among the biggest causes of personal bankruptcy. The general price for treatment is $100,000 a year. So out of control and damaging is this issue that financial toxicity and bankruptcy must now be regarded as major and probable side effects of cancer treatment. People’s fears and anxieties are being exploited. Middle class patients aren’t eligible for financial assistance. Pathetically, people are taking half the recommended doses of the newest and most effective treatments as a way of getting, at least hopefully, some treatment benefit. How many have died because they couldn’t afford treatment?

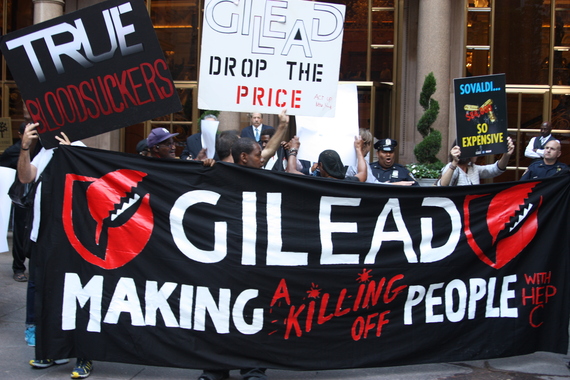

In 2013, the New York Times published an article, “Doctors Denounce Cancer Drug Prices of $100,000 a Year.” The cancer specialists interviewed here and on 60 Minutes were unanimous in their denunciation of capricious drug pricing, which one of those on the 60 Minutes feature described as dictated by “corporate chutzpah.” In response to such criticism, pharma gives a standard defense: The high fees are necessary to cover the costs of research. In this case, because of the widely-seen NYTcriticism, pharma agreed to reduce by 50 percent the prices of the drugs specifically under indictment by the cancer docs.

While it’s true that we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that the pharmaceutical companies are producing new miracle cures and treatments that otherwise might not have come about, and that the costs of research are considerable, in the bigger picture, pharma is nonetheless and indeed making a killing (pun intended) on these medications. As reported in the New York Times , as a result of its sales of Sovaldi, the new miracle cure for hep C, Gilead took in record profits of $10.3 billion in 2014, making it a close runner up to the world’s best-selling pharmaceutical, Humira, the wonder-drug for rheumatoid arthritis, the costs of which can run more than $20,000 a year. Ever wonder why we’re seeing so many advertisements for medications on television? As with any other products, getting the information out there to target populations is unquestionably the best way to boost sales. In other words, the plethora of advertisements for medications is a lot less about improving public health than it is about making bucks.

As criticism mounts, and not so coincidentally as windfall profits already have been made, the prices of the hepatitis C medications are beginning to come down. Alas, any optimism that might be attached to such limited and tentative success is like making incursions on one or two villages overtaken by ISIS and hoping democracy will replace Islamic extremism throughout the land. As characterized by one leading specialist interviewed in the 60 Minutes episode, pharma has rendered drug-pricing “unreasonable, unsustainable and immoral.” The same drugs in Canada and Europe cost 50 to 80 percent less. Meanwhile, our Republican Congress will almost certainly veto any efforts by Obama to regulate the price of drugs.

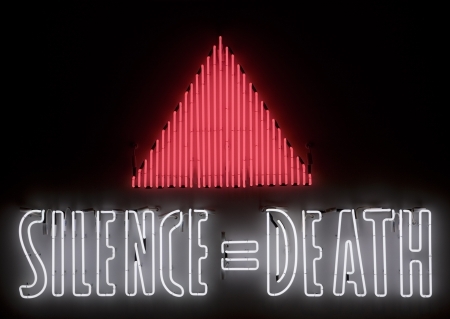

Is pharma complicit in extortion and murder when unreasonable pricing and policies lead to casualties? Leading AIDS activist Larry Kramer certainly thought so, and he is legendary for denouncing as “murderers” and “Nazis” everybody who was not on the front lines of testing new drugs and getting them into patients with HIV/AIDS. Kramer was additionally clear about a subject he returned to again and again: “evil,” which he defined as including sins of omission and silence as well as those more overtly deliberate.

As a result of the war on AIDS led by Kramer, people with HIV and AIDS got treatment despite seemingly implacable early resistance from pharma and its collaborators. In the case of AIDS, pharma lost, at least initially. Clearly, however, questionable research priorities, price-gouging and insurance coverage denials continue to erupt for new treatments for many other illnesses and conditions.

When the ultimate antiviral for HIV is finally developed, the one that can cure AIDS with the success that antivirals are currently able to cure hepatitis C, will there be more all-out battles over pricing and access? Alternatively, will pharma, as Larry Kramer currently believes, deprioritize developing that cure around issues of profit? Does NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease) Director Anthony Fauci really have the power to more decisively lead the final push for curative treatment, as Larry Kramer suggested when he received the first Larry Kramer AIDS Activism Award (4/23/15) of GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis)?

Notwithstanding a second Supreme Court decision in support of Obamacare, it’s clear that health care in the U.S. remains in a state of crisis. Millions of people still don’t have health insurance, and pressures remain great to repeal reforms that have extended even bare-bones insurance benefits to the uninsured and underserved. “Big Pharma,” as it’s evermore widely designated, remains unregulated. Notwithstanding the occasional gesture of assistance to the financially challenged with lottery-like vouchers and participating in some fair pricing coalition negotiations, pharma, insurance companies, lobbies and politicians, especially Republicans — those who stand to gain financially — have done everything in their power to prevent the implementation of anything remotely approximating equitable and humane health care for those who can’t afford costs that have no controls and that have become so exorbitant that they can only be called extortion, comparable to loan-sharking and usury.

It’s no longer shocking to hear stories about people who die of treatable cancer and other conditions because they had no health insurance or, if they did, because they couldn’t pay the uncovered costs. By 2009, it was estimated that 45,000 preventable health care deaths were occurring annually. The ACA has doubtless reduced that number, but by how much, and can ACA coverage continue to endure the relentless incursions of for-profit interests? At what point do the rest of us do what Kramer and the AIDS activist organization he founded and led, ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) did and are still doing: point fingers, name names, carry placards, stage boycotts, encourage divestment, and alert the media to planned demonstrations?

With ACT UP, demonstrations, protests, boycotts and civil disobedience established a track record of success for confronting unfairness and complacency in health care, especially with AIDS but beyond HIV/AIDS to hep C and other fronts. But ACT UP no longer has the resources, prime-time media attention and constituency support to have as much impact. To more effectively reign in pharma for access and costs of treatments such as those for HIV, hep C and cancer, representatives of the different affected constituencies — from those with histories of drug addiction and those in drug addiction treatment, from the poor who have no health insurance to middle-class patients whose insurance coverages are limited — would have to come together on a larger, broader and more determined scale than we have to date.

Like the new curative treatments for hepatatits C, ACT UP was another of the most important developments in the history of medicine. For the level of its achievement in unprecedented grass-health care activism, and the saving of hundreds of thousands of lives by facilitating the rapid development and distribution of unprecedentedly successful antiviral therapies for HIV/AIDS, ACT UP deserves the Nobel Prize. But don’t count on that to happen anytime soon.

Sadly, such activism is still urgently needed, not only for AIDS, hepatitis C and cancer, but for the entire American health care system. For that to happen, the individuals and groups that would need to come together in much greater numbers and organize a lot more effectively turn out to be nothing less than the great aggregate of humanity, the history of which is the title subject of Larry Kramer’s magnum opus: the American people. (The American People, Volume 1: Search For My Heart, was published by Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, April 1, 2015)

[“source – huffingtonpost.com”]